Ask a Designer: How do I buy light bulbs?

It’s come to my attention — via viral tweets, conversations in the hardware store lighting aisle, and nighttime suburban drives — that the public at large is struggling with light bulbs.

It worries me a little that discussion about LED bulbs in particular seems stuck in about 2005 - “they flicker, the color is all wrong, nothing will ever compare to the beloved incandescent!” Bzzzt. Wrong. The last two decades of LED development has been so impressive that my college textbook is almost entirely out of date. If you think you hate LEDs categorically, you’ve only purchased low-quality ones.

And this brings me to what I’ve begun to believe is the real issue: no one has ever taught anyone anything about lighting, and the technology shift only made it worse. Very few people understand what they’re looking at when they read a light bulb package, and I’m going to fix that. Class is in session.

I’m going to explain a few key elements of lighting: color (temperature), brightness, wattage, and color rendering index. Then I’ll give some tips on lighting your home and address some myths/FAQs.

Part 1: Translating a Light Bulb Package

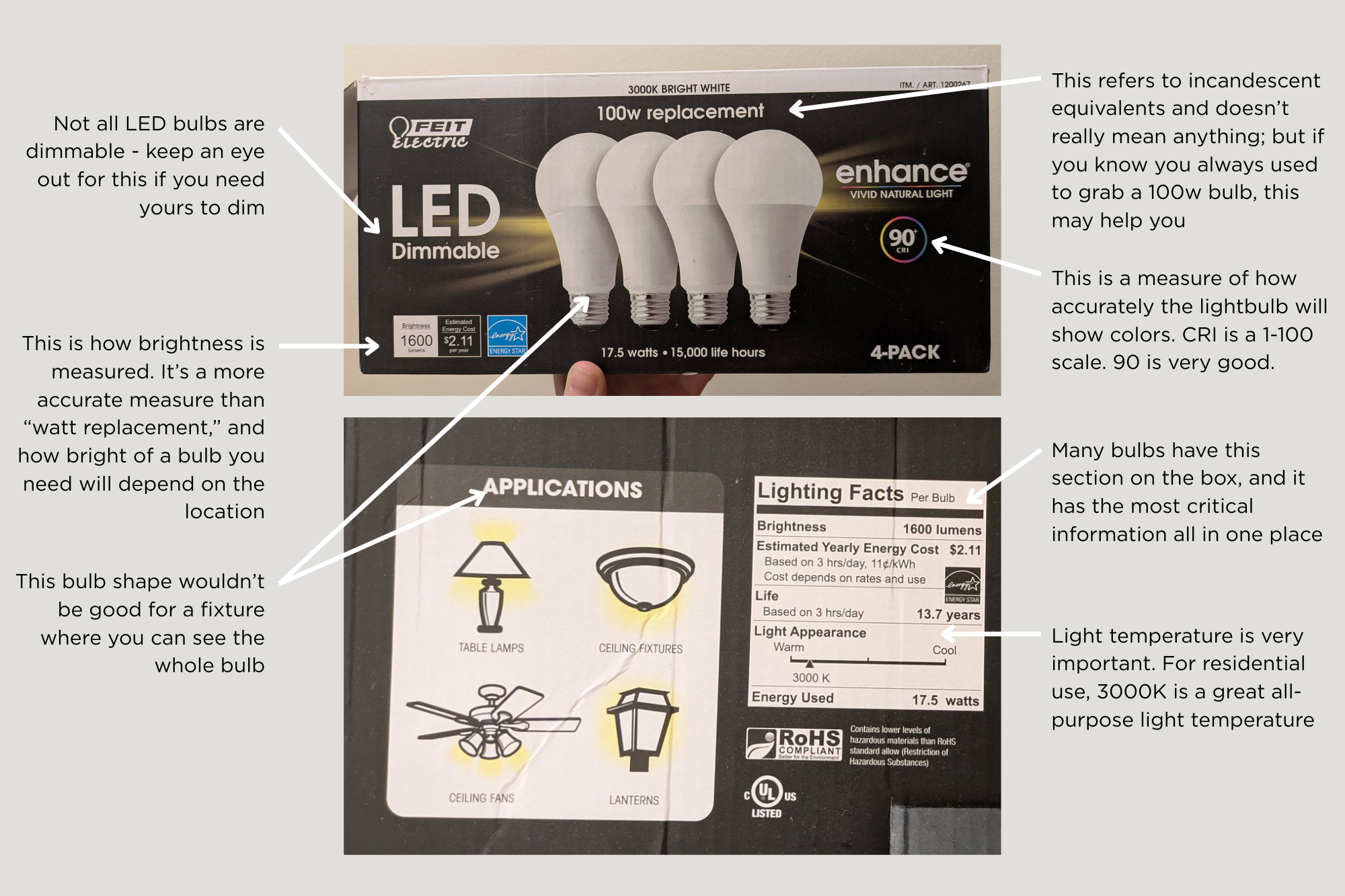

When you’re in the store reviewing light bulbs, you need to understand the information they’re giving you. Let’s dissect and discuss:

Temperature: this is the single biggest spot where people are messing up and making their homes worse, and I mostly blame it on the packaging.

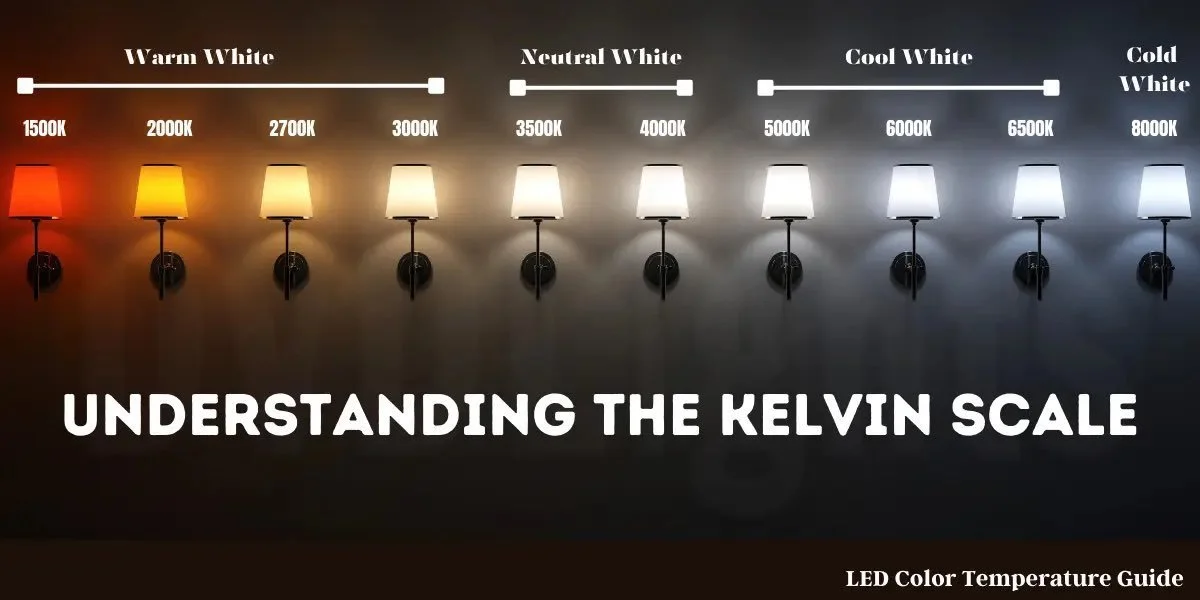

Light temperature is measured in Kelvin; that’s the K suffix you will see on the package. Somewhat counter-intuitively, a lower temperature is a warmer light (write that down and don’t forget it).

Because people hate technical stuff, manufacturers have resorted to shorthand terms like “soft white” and “daylight” rather than emphasizing the color temperature, and the results are bad! People love daylight, so of course they are choosing it; but, and this is critical: lightbulbs are not the sun. We don’t need them to be the sun. Sunlight during the day is around 5000K-6000K, and it does not look good indoors. Please, I beg of you: do not choose a bulb over 3500K for your home.

The photo below is the most accurate I’ve found for illustrating the Kelvin scale. I prefer 3000K for my home: it’s neutral light that feels clean but still warm with no yellowish cast. However, 2700K is similar and more easily found in the market. For commercial projects, I most often use 3500K and will dip down to 3000K for lamps and accent fixtures. I’ll get into mixing color temperatures in the design section, but I prefer not to mix lights that are more than 500K apart. It looks like a mistake, just “off” enough to feel wrong even if you can’t identify why.

Brightness: this is a measure of how much light is put out from a single bulb, and it is measured in lumens. This has always been the case, but during the reign of incandescents, watts became shorthand for brightness. Everyone knew that they grabbed a 60 watt bulb for that specific lamp; they understood what that meant and how bright it was. In reality, a 60 watt incandescent puts out about 800 lumens, but this wasn’t very well communicated.

How bright you want your bulbs to be is a personal decision and should be a factor of what you’re doing in the room and how many sources of light you have. I’ll get into lighting design further in the post.

Wattage: this is a measure of how much energy the bulb uses to create that brightness, and it’s pretty straightforward. LEDs are significantly more efficient than their incandescent, fluorescent, or CFL counterparts, which is why they’re being adopted so widely. When the shift to LEDs began to happen in earnest, manufacturers started putting verbiage like “75 watt equivalent” onto the packaging, but this is nonsense, and everyone can tell because right there next to it, the box says “13 watts of energy used.”

Critical takeaway here: watts and brightness are not the same thing, and they never have been, though there is a more direct relationship between the two with incandescent technology. It’s important to understand both, but wattage isn’t something you can select for. You’re choosing how bright you want the bulb to be, and the energy needed to create that brightness is what it is.

Color Rendering Index: this is not always included on the box, but it’s good to understand it theoretically. Color Rendering Index (CRI) is a measure of how accurately a light source shows colors compared to daylight. It’s measured on a scale of 1-100, and higher is better (read more here, including about some of the limitations of this measure). Incandescent bulbs naturally have a very good CRI because their light spectrum is very similar to that of daylight; fluorescent bulbs tend to be pretty bad. Anything above 80 is acceptable, but it’s preferable to be in the 90s.

Part 2: Frequently Asked Questions

So… what lightbulb do I buy?

I am not a lightbulb testing specialist, but I like the GE Relax bulbs (2700K: Amazon) and Feit Electric bulbs (3000K Amazon | Home Depot). Another tech to consider is “dim to warm,” where a lightbulb gets warmer in temperature the more it is dimmed. I’m not personally into this, but a lot of people are, and I’ve read good things about this Phillips bulb, which dims from 2700K to 2200K (Amazon)

“I’ve read that I should use different light temperatures in different areas of my house - what should I use, and where should I use it?”

I see this advice a lot, and I think it’s wrong. If you really love changing light temperature room to room, knock yourself out. But my opinion is that it’s unnecessarily fussy, and as a bonus, now your home looks funny from outside at night. Some people prefer cooler lighting for detailed work, so I can see an argument for going a bit cooler in a workshop or a lamp above where you embroider or paint. But as a basic recommendation, I go with 3000K bulbs for homes.

“I’ve tried LED bulbs, but they flicker and that drives me insane. What is going on with that?”

There are a few reasons LED bulbs flicker: the driver, which regulates power, can fail; if it is going to fail, it will usually be pretty early in the life of the bulb. A dimmer switch that isn’t compatible with the bulb — or trying to dim a bulb that is not dimmable — can cause flicker. Faulty wiring and inconsistent power supply can also cause flicker. But in my experience, it’s most commonly associate with cheap bulbs. There are some bulbs that are a great value (the Feit bulbs above are very cost-effective), but you often get what you pay for.

“I want to use warm bulbs to make my house cozy. What’s wrong with that?”

Nothing! Use whatever you’d like. But there are many ways to achieve coziness, and a warm light temperature is only one factor. In my experience, coziness has more to do with the quantity of light sources and their relative brightness. The reason Christmas trees add such ambiance to a room is that they are covered in tiny, dim lights. Humans respond strongly to this. Same goes for a patio covered by string lights. Similarly, a room full of candles doesn’t feel romantic and warm just because firelight is so warm: it’s also because a room with many low-level light sources is inviting.

A similar effect can be created more practically year-round with dimmable lamps. A good rule of thumb is at least three dimmable non-ceiling light sources in a room: sconces, floor lamps, table lamps, picture lights, etc. It’s not as efficient as one very bright overhead light, but it’s a much better vibe.

Take a look at this video, and note just how many sources of lights there are in his home:

I hope this has been helpful! If you have questions I haven’t addressed, feel free to drop them in the comments and I can add them in later.